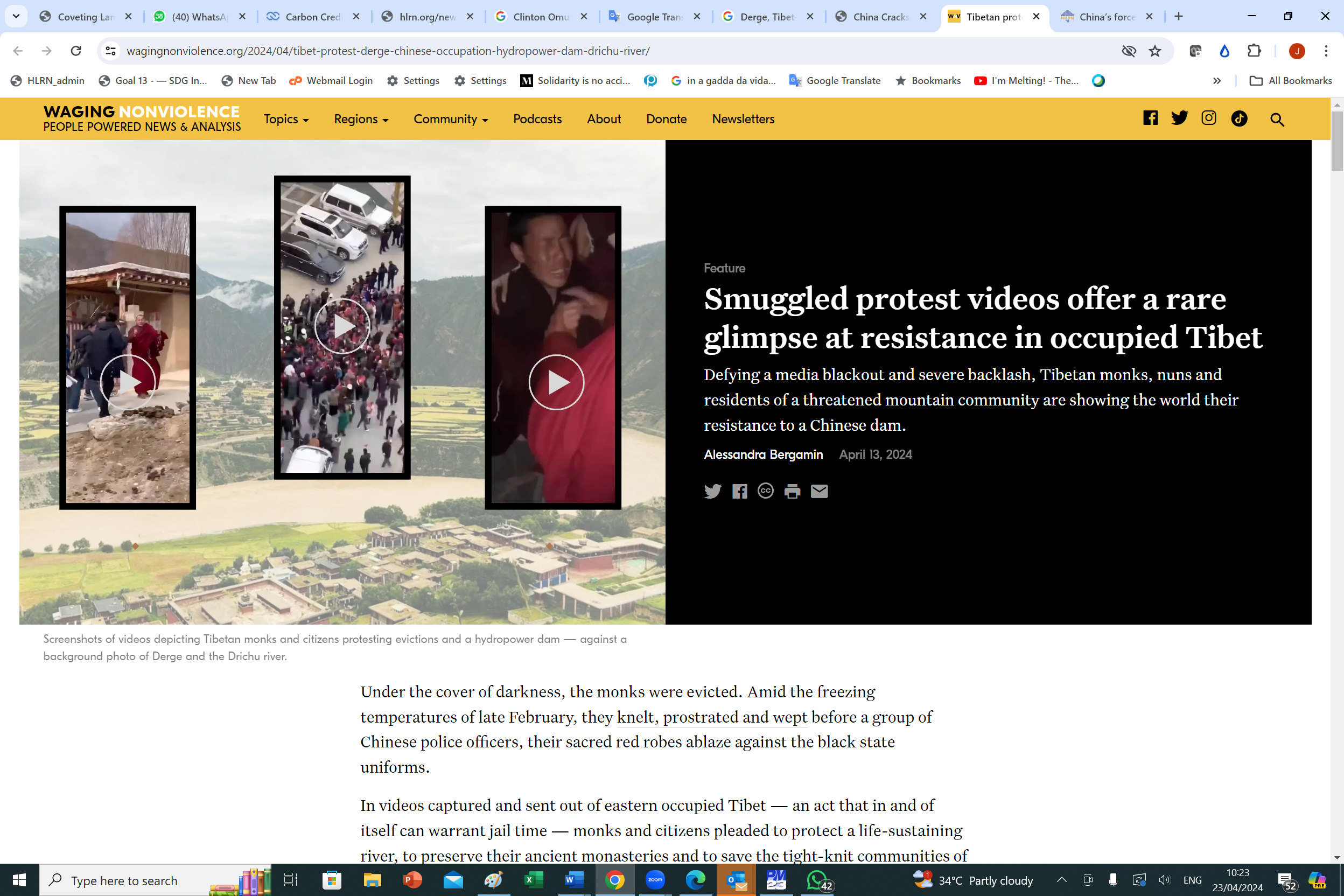

Smuggled protest videos offer a rare glimpse at resistance in occupied Tibet

Defying a media blackout and severe backlash, Tibetan monks, nuns and residents of a threatened mountain community are showing the world their resistance to a Chinese dam.

Under the cover of darkness, the monks were evicted. Amid the freezing temperatures of late February, they knelt, prostrated and wept before a group of Chinese police officers, their sacred red robes ablaze against the black state uniforms.

In videos captured and sent out of eastern occupied Tibet — an act that in and of itself can warrant jail time — monks and citizens pleaded to protect a life-sustaining river, to preserve their ancient monasteries and to save the tight-knit communities of Derge, in the mountainous Kham region. But by day, and by night, outside of the monasteries and inside the town centers, monks, nuns and residents were arrested one by one. In the following weeks, the list of alleged crimes would run long, but on Feb. 23 more than a thousand Tibetans were arrested for protesting.

Drimey, a Tibetan in exile who has asked to be identified by his first name only, watched these videos in horror. Monks are highly respected in Tibet, but what he saw — desperate people begging on their knees — was saddening, almost denigrating, to someone from a highly reverent culture. Hailing from the town of Wongpo Tok (one of the sites of the arrests), Drimey crossed the Himalayas on foot in 1999 to pursue Tibetan and religious studies not accessible in his home under occupation. Now, he is watching from afar as his community is criminalized, his town is submerged and his religion is desecrated.

“I have known those mountains and those roads,” he said through a translator. “I have known everything.”

About a week before the arrests in early February, just across the mountain from Wongpo Tok, some 300 people gathered outside the Derge County Seat — home to the Chinese Communist Party’s provincial office — to protest the construction of the Kamtok Hydropower project. Slated to straddle the banks of the Drichu River, the headwaters of Asia’s 3,915-mile Yangtze River, the hydropower dam will not only strangle the river’s winding route but forcibly displace thousands of Tibetans. According to a 2019 report from the International Campaign for Tibet, the hydropower project is one of 25 dams set to carve through the Tibetan plateau and generate “clean” electricity.

A parallel situation is also unfolding in Amdo county where the Chinese government recently announced plans to relocate the historic Atsok Monastery and surrounding communities to make way for another large-scale hydropower project. Tibetans told Radio Free Asia that in the wake of this news, residents gathered at the monastery to pray while monk leaders were told to accept the relocation plan and promise not to protest.

“These huge dams are not for Tibetans,” said Dr. Lobsang Yangtso, the programme and environment coordinator at International Tibet Network, a global coalition of Tibet-centered organizations based in Berkeley, California. “It’s a colonial mentality where these resources are to be consumed by mainland China.”

Top of Form

Bottom of Form

Tibet has a long history of nonviolent resistance dating back to 1959, around 10 years after China’s occupation. Under extreme repression, the country’s monasteries have become a driving force behind nonviolent actions including peaceful demonstrations and poster campaigns that, in recent years, have become less frequent given the grave consequences.

While it’s largely unknown how the February protests were organized, videos sent out of the country have offered a rare glimpse into nonviolent resistance in occupied Tibet in 2024. In video clips, Tibetans can be seen peacefully gathering, chanting and, in some instances, holding up two thumbs — a gesture that expresses an appeal for pity. In others, Tibetans are shown waving the Chinese national flag. According to Tenzin Norgay, a research analyst at International Campaign for Tibet, this was an attempt to show that they are not separatists, as they are likely to be labeled, but simply expressing their concerns and desire to be heard.

That desire for discussion is internationally known as free, prior and informed consent, or FPIC — a right enshrined in the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and applicable to Tibetans. While this is an imperfect process in much of the world, China has among the highest levels of development-related displacement despite resettlement being labeled as 100 percent voluntary. In the same way that protest is silenced and information restricted under Chinese occupation, “consent” is usually achieved without consultation and through coercion. True FPIC is an “absolute luxury,” said Norgay, and there are few mechanisms through which Tibetans can voice their concern or opposition to state projects and policies.

Globally, hydropower projects from Honduras to the Philippines have been a violent frontline for environmental defenders. According to a 2019 study drawing data from the Global Environmental Justice Atlas, resistance to hydropower projects is met with a similar pattern of violence as other extractive industries, including oil and mining. In 2009, six women in Tibet were shot during demonstrations against a hydropower project according to the Tibetan government in exile, now based in Dharamshala, India.

In Derge, more recently, some of the charges enumerated by the Chinese government in the wake of these recent demonstrations include fines and imprisonment for protesting against government initiatives, distributing pamphlets and shouting slogans.

“When we think of environmental defenders, there is no more visceral scene than hundreds of Tibetans begging on their hands and knees to protect their environment knowing full well that they’re risking arrest and imprisonment,” said Topjor Tsultrim, the communications coordinator at Students for a Free Tibet, an organization that works in solidarity with the Tibetan struggle. “It’s the same issue and the same mindset as defenders in the Amazon coming up against the impossibly large forces of government or corporations.”

In Derge, as internet access became even more restricted and cell phones were confiscated, arrested Tibetans — including those who had simply enquired about their loved ones — were told to bring their own bedding and tsampa (a barley flour staple).

The sheer number of arrests in a single day meant detainees could not be imprisoned in local jails but were sent across occupied Tibet and into China’s Sichuan province. Jail conditions are poor with overcrowded cells, scarce food and, in the winter, a cold that can strike to the bone. In these conditions, one-on-one interrogations are constant and physical violence — such as beatings, thrashings and, in extreme cases, torture — is used as a tactic to elicit information.

According to reports out of Tibet, several detainees were beaten so badly they required hospitalization. The goal of these interrogations is to single out the alleged organizers, Norgay said, and it’s likely officials already have. While there are no specific figures, most detainees are believed to have been released in late March, except for a village official and the administrator of the Wonto monastery.

“The Chinese authorities don’t like organizers so I’m expecting they will get around 10 years in prison, maybe even more,” he said. “They are thought of as the ringleaders who are basically revolting against the state.”

Despite the repression that followed these protests, Tibetans — both in the occupied country and in exile — know what is at risk should the hydropower project continue. The Wongpo Tok of Drimey’s memory is one of summertime wildflowers, free-flowing rivers and peaks that stretch towards the sky. It is a place where the farmers cultivate their crops twice a year, where the nomads herd their cattle across the grasslands and where every family has more than a hundred yak and geese. Monasteries are centers of language, culture, religion and education. Lamas are venerated, mountains revered. The Drichu River is a source of life. For Drimey, the community of Wongpo Tok is pleasant, prosperous and alive. But relocation, Drimey said, will destroy the community, as well as knowledge of the land, mountains and waters passed down from one generation to the next.

“People have a strong attachment to the land,” Drimey said. “If it goes underwater, they will lose everything forever.”

For many communities across Tibet, everything has already been lost. In recent years, Chinese policies operating under the guise of “poverty alleviation” or “ecological restoration” have been leveraged to displace thousands of Tibetans from their ancestral homelands. Two years ago, more than 17,000 people were resettled nearly 250 miles from their community as part of the state’s “very high-altitude ecological relocation plan.”

The policy, introduced in 2018, stipulates that by 2025, 130,000 Tibetans will have been relocated. Bused en-masse to government-constructed housing akin to “boxes,” according to Norgay, forced resettlement means the loss of traditional farming knowledge, the erasure of nomadic ways of life and the unmooring of a strongly Buddhist people from the center of their faith.

“Tibetan towns are built around monasteries,” Tsultrim said. “They are the heartbeats of the community.”

According to reports, the Kamtok Hydropower project is expected to submerge six monasteries, including Wonto, the scene of some of the arrests. These monasteries, long protected and preserved by monks and lamas, are not only the spiritual center of a community but also home to Tibetan Buddhist murals dating back to the 13th century.

After China fully occupied Tibet in 1959 and throughout China’s Cultural Revolution, more than 97 percent of monasteries and nunneries were destroyed, according to the 10th Panchen Lama, writing in 1962. The destruction of these ancient monasteries is more than a cultural and religious loss — it’s another means of dismantling what it is to be Tibetan.

“For the state, a dam is an important symbol of modernity,” Norgay said. “But for local Tibetans, these cultural artifacts — monasteries and murals — signify their identity.”

At the heart of that identity is a way of life that for centuries has preserved the delicate balance of the Tibetan plateau and what is often known as the “Third Pole.” Glaciers in Tibet act as a water storage tower for Asia, holding the third-largest store of water ice in the world. This glacial melt then feeds some of south and southeast Asia’s largest rivers, including the Ganges and the Mekong, which around 1.5 billion people rely upon.

Large-scale dams across Tibet, including the potential Kamtok, also drain the Tibetan plateau to generate electricity. But Tibet is a country on the frontlines of climate change, perhaps more so than any other, as temperatures are rising two to four times higher than the global average. Because of that, glaciers are melting rapidly, threatening the future water supply while below-average rainfall has already impacted China’s current hydropower generation despite the constant construction of more dams.

This investment in hydropower, as well as solar and wind, is part of China’s plan to transform itself from the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gasses to a leader in climate change action. By 2030, the Chinese government plans to peak carbon emissions and become carbon neutral by 2060. Alongside clean energy investments, the government has been quietly mining the plateau for minerals such as gold, copper and lithium, which are essential to the green transition. These extractive processes — protected by checkpoints, prohibited for Tibetans and often undertaken at night — can pollute the soil, air and water, said Yangtso from the International Tibet Network.

Given that Tibet largely exists in a media blackout and the consequences of sending even a photo out of the region are dire, it’s difficult to monitor the environmental impacts of these projects. But the plundering of resources — from water to lithium — also raises the question: Is climate change mitigation under occupation simply a greenwashing of human rights abuses?

“There’s no value of the Tibetan people and no respect for traditional knowledge or the ecosystem,” Yangtso said. “The Chinese government just wants to exploit the natural resources as much as possible. They see Tibet as a solution for their global climate goals.”

At an international level, the recent protests and human rights abuses have not gone unnoticed. Tibetans in exile, from northern India to London, protested in solidarity with those arrested. Thousands more across Europe and the U.S. joined for Tibetan Uprising Day, which commemorates the lives lost during the 1959 protests against China’s occupation. Thanks to the efforts of organizers, a new bipartisan House resolution recently recognized the 65th anniversary of the Tibetan Uprising Day and condemned the human rights violations in Derge.

While there is some uncertainty as to whether the Kamtok Hydropower Project will be constructed, organizations have continued their advocacy work through petition writing and lobbying Western governments to pressure China. Meanwhile, the videos captured in Tibet, which people knowingly risked personal safety to send outside of the country, have circulated on social media and in international news. It is this assertion of autonomy under occupation that has not only revealed the cost of protest under repression but served as a reminder that — despite the consequences — there remains power in dissent.

“This dam may be built, they may get arrested, but one thing within their control is to get this news out into the world,” Tsultrim said. “To show people that this is the reality of what’s going on inside China’s occupied Tibet, this is the reality for Tibetans.”

Photo: Excerpts of screenshots showing monks and other citizens protesting eviction, with Dege and Drichu River in the background.